Long before Europeans and their descendants tagged the Lower Mississippi River valley with a cornucopia of artificial lines, forming states, and counties, and meridians and so forth, the area already had a remarkable human history. Native Americans left behind laboriously-constructed earthen mounds. Those served a variety of residential, ceremonial and funereal purposes all along the river and across the surrounding terrain.

Wickliffe Mounds

We stopped first at Wickliffe Mounds near the confluence of the Mississippi and Ohio Rivers. It fell just barely on the Kentucky side of the border (map).

Historical Context

The Middle Mississippian cultural group that selected this site didn’t choose it accidentally. They clustered on high ground well above the floodplain at the meeting of two mighty rivers. Thus they occupied their bluff from around 1100 to 1350 as noted by artifacts left behind.

Wickliffe never became more than a small village with a few homes clustered around a central plaza. Inhabitants then added a burial mound and a ceremonial site. As noted by Kentucky State Parks,

“Peaceful farmers, they grew corn and squash, hunted in the neighboring forests and fished the river; they made pottery from shell-tempered clay with elaborate designs and decorations, they participated in a vast trade network up and down the rivers, they had stone, shell and bone tools, they had a complex chiefdom level society, they lived in permanent style houses made of wattle and daub, and they built flat topped platform style mounds.”

Exploitation and an Eventual Appreciation

An amateur archeologist purchased the site in the 1930’s. Then he turned it into a degrading roadside display called “Ancient Buried City.”

He disinterred the remains of the original inhabitants from their burial mounds as an attraction for gawking tourists. It took the passage of the Native American Graves Protection and Repatriation Act in 1990 to compel the removal of these ancient skeletal remains from public view. Eventually the property passed to Murray State University. Only then did archaeologists conducted a proper archaeological reviews.

The State of Kentucky became the next and final owner of the property. Fortunately the state reburied all bodies of original Mound Builders under the supervision of the Chickasaw Nation. However, that didn’t happen until 2011.

The state removed every exploitative vestige of Ancient Buried City. Nonetheless, one could always visit the smoke shop and souvenir stand across the street, I suppose, if one were somehow nostalgic for those days.

Winterville Mounds

We’d hoped to visit Winterville Mounds outside of Greenville, Mississippi (map). Then the skies cracked opened and it rained so hard that we holed-up in our hotel room for a full afternoon. Actually that turned out to be a good idea because we felt completely exhausted by that point. I couldn’t find a decent photograph of the mounds so let’s stick with the Street View link. Double fail.

Winterville was a Lower Mississippian site settled around the same basic time as Wickliffe. As the State of Mississippi explained,

“Archaeological evidence indicates that the Indians who used the Winterville Mounds may have had a civilization similar to that of the Natchez Indians, a Mississippi tribe documented by French explorers and settlers in the early 1700s. The Natchez Indians’ society was divided into upper and lower ranks, with a person’s social rank determined by heredity through the female line. The chief and other tribal officials inherited their positions as members of the royal family. The elaborate leadership network made mound building by a civilian labor force possible.”

I’d like to come back for another attempt should I ever find myself in the area. The descriptions sounded pretty impressive.

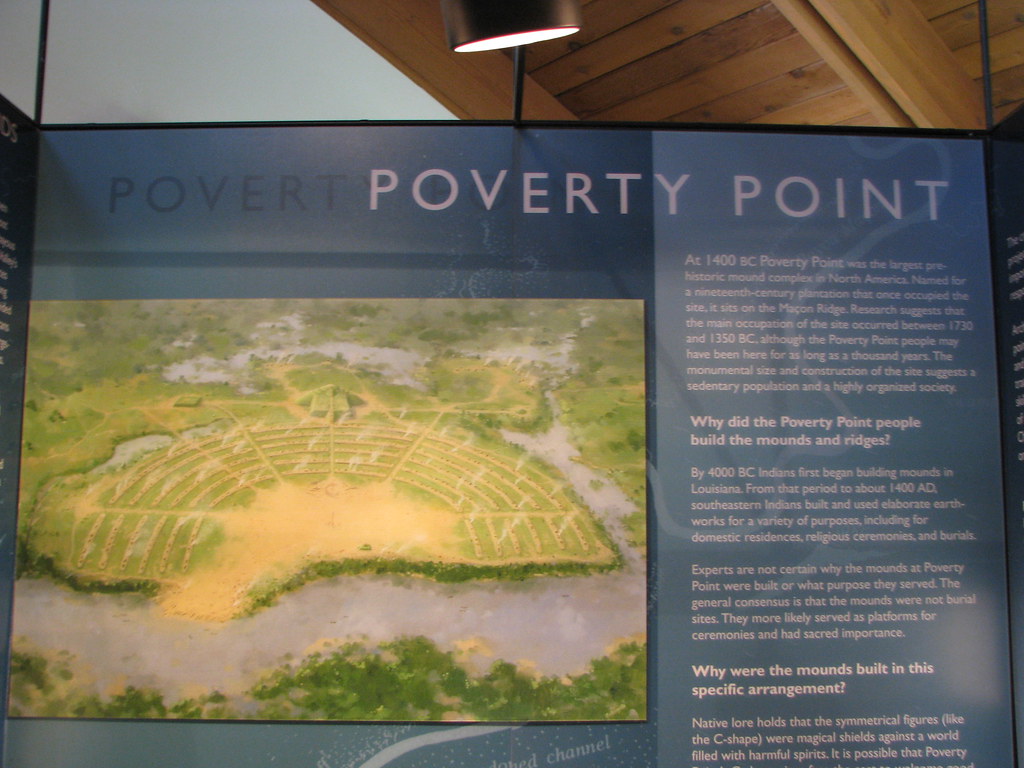

Poverty Point

Poverty Point was a considerably more colossal site, located in what is now northeastern Louisiana (map). This was also a much older site, constructed during the Archaic Period and peaking about 3,000 years ago. Poverty Point was one of the largest sets of mounds in North America, covering nearly a thousand acres. The National Park Service estimated that its construction was “the product of five million hours of labor.”

It was so massive that no single photograph from ground level could do it justice. The photo I took and posted above showed just a portion of a mound called the Bird Mound. However I didn’t have the camera angle to show the six concentric crescents aligned in front of this earthen monolith that formed a central plaza facing Bayou Marçon. It’s all best appreciated from the air. The structure showed up decently in Google Maps’ Terrain View. Unfortunately, Google disabled the embed function in the “new and improved” maps. Instead I’ll post a photo I took in the Visitors Center.

The Bird Mound was the small square at the middle-back of the crescent.

These pre-Columbian Native Americans left behind scores of mounds in what we now call the Central and Southern United States. It’s a little understood piece of history with a level of sophistication not always appreciated. Mounds that weren’t desecrated for souvenirs or destroyed by farmer’s plows were true survivors. Thus, they told a story of a highly advanced culture that existed before Europeans set sail for the Americas.

Leave a Reply